Senior Care: A Guide to Understanding Support Options for Older Adults

Outline

– Why senior care decisions matter now, and how to talk about values and goals

– How to assess needs using ADLs, IADLs, safety, and cognition

– In‑home care, technology, and day programs: what fits and when

– Community and residential options: differences, costs, and trade‑offs

– Paying for care, legal planning, coordination, and a practical next‑step checklist

Why Senior Care Decisions Matter Now: Values, Timing, and Starting the Conversation

Older adulthood is changing fast. Global agencies estimate that by 2050 roughly one in six people will be over age 65, and the number of adults aged 80+ will more than triple. Longer lives are a gift, yet they bring practical questions: how to stay safe, independent, and socially connected; how to manage chronic conditions without losing daily joy; and how families can share responsibilities without burning out. The stakes are human and immediate. Delaying decisions often narrows choices after a fall, hospitalization, or a sudden change in memory. Starting early keeps options open, reduces crisis costs, and allows the older adult’s voice to lead the plan.

Begin with values before services. Ask what matters most: staying in a familiar home, being near friends, keeping a pet, walking to faith or community events, or having fewer responsibilities like yardwork. These priorities shape every later choice. A short, candid conversation can set a collaborative tone: “What do you want your days to look like six months from now? What worries you most about living at home? Where would you want help first?” Many families find that naming fears lowers tension; it is easier to talk about transportation or meal help than to jump straight to major moves.

Evidence supports early planning. Studies of care transitions show that coordinated support lowers re‑hospitalization and improves satisfaction. Surveys of unpaid caregivers consistently find high rates of stress and sleep disruption, yet stress drops when tasks are shared and expectations are clear. Practical steps to open the dialogue can be simple:

– Choose a calm time and neutral place, not right after a crisis.

– Bring a short list of concerns and one positive goal for the next month.

– Agree to test small changes (like a weekly grocery delivery) before debating bigger moves.

Think of senior care like building a layered safety net. The first layer is information and a shared map. The second is small supports that preserve autonomy. The third is backup plans for “what if” moments. When you anchor plans in values, you avoid the common trap of buying services that solve the wrong problem. That clarity sets up the next step: a practical assessment of needs.

How to Assess Needs: ADLs, IADLs, Safety, and Cognitive Health

Assessment turns vague worry into a clear picture. Professionals often organize needs around Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADLs). ADLs include bathing, dressing, toileting, transferring, continence, and eating. IADLs include cooking, shopping, managing medications, using transportation, handling money, and housekeeping. A simple scorecard—what is independent, what needs set‑up help, what needs hands‑on assistance—can reveal gaps that a family may have normalized.

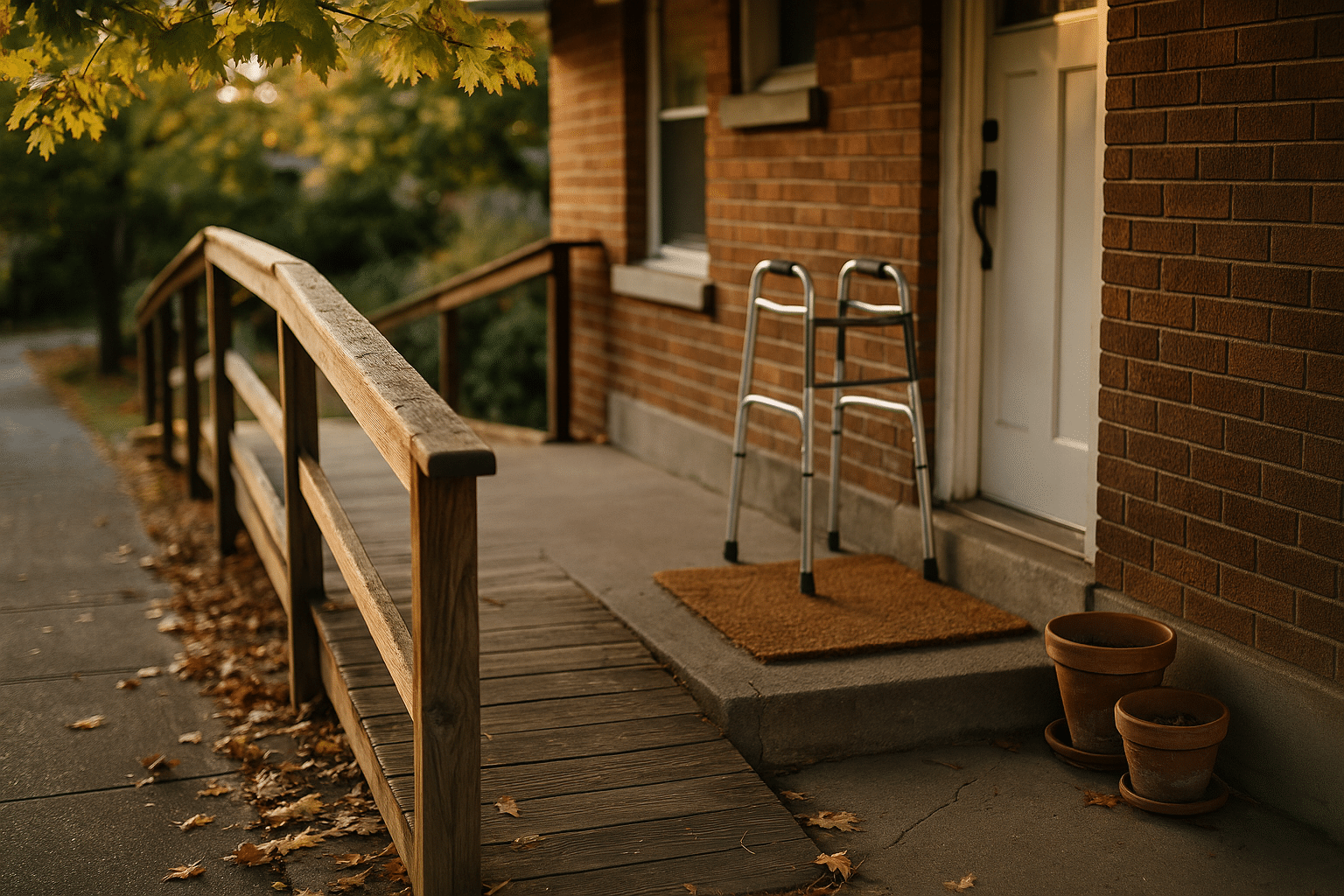

Layer in safety. Home risks often accumulate quietly: loose throw rugs, dim hall lighting, no grab bars, cluttered stairs, and a too‑high bed height. A brief walk‑through can help:

– Entrances: Is there at least one step‑free entry? Are railings sturdy and easy to grip?

– Bathroom: Are there grab bars anchored into studs? Is the shower floor non‑slip?

– Lighting: Are pathways to the bathroom and kitchen well lit at night?

– Kitchen: Are heavy pots stored at shoulder level? Are smoke detectors working?

Small fixes—contrasting tape on stair edges, raised toilet seats, handheld showerheads—reduce fall risk without changing the feel of the home.

Cognitive health is equally important. Occasional forgetfulness happens to everyone; patterns are what matter. Red flags include repeated medication errors, getting lost on familiar routes, unopened mail piling up, scorched pans, or new scams slipping through. A primary clinician can screen memory and attention, but families can also note changes in mood, sleep, and social engagement. Mild cognitive changes may only require structured routines and simplified bills; more significant changes suggest a need for medication oversight, financial safeguards, and, at times, supervised living.

Don’t skip medical complexity and mobility. Track diagnoses, medications, and recent hospitalizations. Ask: Is pain controlled? Are there wounds, shortness of breath, or new weakness? Are there mobility devices that are the wrong size or gathering dust? Data from rehabilitation research shows that properly fitted walkers, exercise programs tailored to ability, and home‑based physical therapy reduce falls and maintain independence.

Turn assessment into a written plan. Summarize the top three risks and the top three goals, assign owners, and set a date to review. Example: “Goal—safer bathing. Actions—install grab bars, add a shower chair, schedule two supervised showers weekly. Review in four weeks.” Clear targets help you compare support options with purpose rather than guesswork.

In‑Home Support: Caregiving, Services, Tech, and Home Modifications

For many, staying home is the first choice. The good news is that in‑home care can be flexible, from an hour of help with breakfast to comprehensive daily care. Common building blocks include personal care aides, homemaker services, home‑delivered meals, visiting clinicians for skilled needs, and adult day programs that offer supervision and activities during the day. In the United States, hourly rates for non‑medical home care often land in the mid‑to‑high twenties, varying by region and training; skilled nursing or therapy visits typically cost more per visit but are task‑specific. Local nonprofit agencies sometimes supplement these services for those with limited income.

Combine services with practical modifications. Many falls happen in the bathroom and at thresholds, not on dramatic staircases. Helpful upgrades include:

– Grab bars anchored into studs near the toilet and inside the shower.

– A low‑profile shower lip or a roll‑in conversion if mobility is limited.

– Lever‑style door and faucet handles to reduce hand strain.

– Motion‑sensing night lights to guide the path to the bathroom.

– A contrasting strip on stair edges and no‑skid mats under area rugs.

Evidence from home safety studies shows these changes reduce injuries and caregiver strain while keeping routines familiar.

Technology can extend independence when chosen for a real problem—not because it is trendy. Options range from simple pill organizers and large‑print calendars to sensors that alert to stove use or door openings, voice‑controlled reminders, and personal emergency response pendants. A few guiding questions prevent expensive mismatches:

– What single task is hardest today, and will this tool make it easier tomorrow?

– Who will maintain batteries, Wi‑Fi, or updates?

– Can the device be used with one button or a clear voice prompt?

– What happens if it fails—what is the backup?

Caregivers also need care. Surveys routinely find high rates of anxiety, back strain, and lost work time among family caregivers. Respite is not a luxury; it is a sustainability strategy. Adult day programs provide socialization, supervision, and meals for a daily fee that is generally lower than in‑home one‑to‑one care. Short‑stay respite in residential settings can cover vacations or recovery periods. Support groups, skills training, and counseling improve outcomes for both caregivers and older adults. When in‑home support is layered thoughtfully—people, tools, and simple home changes—it can postpone or avoid moves and keep dignity at the center.

Community and Residential Options: Comparing Settings, Services, and Trade‑Offs

Community and residential options exist on a spectrum, and the right fit depends on care needs, preferences, and budget. At one end, independent living communities focus on convenience and social life: private apartments, shared dining, housekeeping, transportation, and activities. They do not usually include hands‑on care, but in many areas residents can hire in‑home aides separately. Next, assisted living adds help with ADLs such as bathing, dressing, and medication reminders, plus meals and 24‑hour staff on site. Memory care communities are designed for people living with cognitive impairment, with secured areas, simplified layouts, and structured, calming routines. Skilled nursing facilities provide round‑the‑clock nursing, rehabilitation, and complex medical management after hospital stays or for ongoing needs.

Cost varies widely by region and level of care. National surveys commonly report monthly medians in the range of a few thousand dollars for assisted living, with memory care typically higher due to staffing ratios and security. Skilled nursing often costs several thousand more per month for a semi‑private room, and private rooms cost beyond that. Independent living is often priced similarly to market‑rate senior apartments with service packages layered on. It helps to compare apples to apples by converting estimates to a “per day” figure and including what you currently spend on housing, utilities, transportation, groceries, and home maintenance.

Quality is about fit, staffing, and culture. During tours, look and listen:

– Are residents engaged, or is the TV the main activity?

– Do staff greet residents by name and at eye level?

– Are hallways free of clutter and bathrooms clean, with grab bars properly placed?

– Can the community describe how it handles falls, changes in condition, and family communication?

Ask about staff training, turnover, and how care plans are reviewed. Request a sample activity calendar and a menu. A community that invites you to visit at different times—mornings, evenings, weekends—signals confidence and transparency.

There are trade‑offs. Home offers familiarity and control but may require orchestration of multiple services. Assisted living simplifies daily life but may feel less private. Memory care prioritizes safety and predictability; it can be more structured than some families expect, but that structure reduces distress. Skilled nursing provides intensive care, yet the environment is clinical. The goal is not a perfect choice; it is a choice that meets today’s needs and can flex as needs change. Building a shortlist, touring, and testing services for a month can replace guesswork with lived experience.

Paying for Care, Legal Readiness, Coordination—and Your Next Steps

Financing senior care is often a mosaic. Most families blend personal savings, retirement income, housing equity, private insurance products, and public benefits that vary by country and state. In the United States, for example, daily home care might run in the mid‑twenties per hour, assisted living often totals a few thousand dollars per month, and skilled nursing runs higher due to clinical staffing. Some public insurance programs cover short‑term skilled care after a hospital stay; long‑term custodial care is typically out‑of‑pocket unless one qualifies for means‑tested programs. Veterans and people with specific disabilities may access specialized benefits. Local aging agencies can map eligibility criteria and help with applications.

Legal readiness prevents chaos. Core documents include a durable financial power of attorney, a health care proxy or medical power of attorney, and an advance directive that spells out wishes for treatment. A simple will, beneficiary updates, and a clear inventory of accounts and passwords reduce administrative stress during transitions. Families sometimes postpone these conversations out of discomfort, but completing documents when capacity is clear protects autonomy. Consider a brief consultation with an attorney who focuses on elder law or estate planning to align documents with local regulations and to discuss options such as trusts when appropriate.

Care coordination is the quiet engine that keeps plans running. Appoint a primary point person and a backup. Use a shared calendar and a single medication list saved in a place everyone can access. Schedule regular 15‑minute check‑ins with the care team—family, aides, clinicians—to review what is working and what is not. Track two or three metrics that matter, such as falls, appetite, sleep, or mood. Small adjustments, made early, prevent big problems later.

Here is a practical, low‑stress action plan:

– Week 1: Hold a values conversation; list top three goals and top three risks.

– Week 2: Complete an ADL/IADL and safety review; schedule needed medical checkups.

– Week 3: Pilot one in‑home service and one home modification; confirm legal documents.

– Week 4: Price at least two community options; compare total monthly costs to staying home.

– Ongoing: Set a 90‑day review to adjust supports as needs change.

Conclusion: Senior care is not one decision; it is a series of manageable steps anchored in what matters most. When you assess needs honestly, match services to goals, plan finances, and keep documents current, you create a wider runway for comfort, safety, and connection. Progress beats perfection, and starting now secures more choice for tomorrow.